|

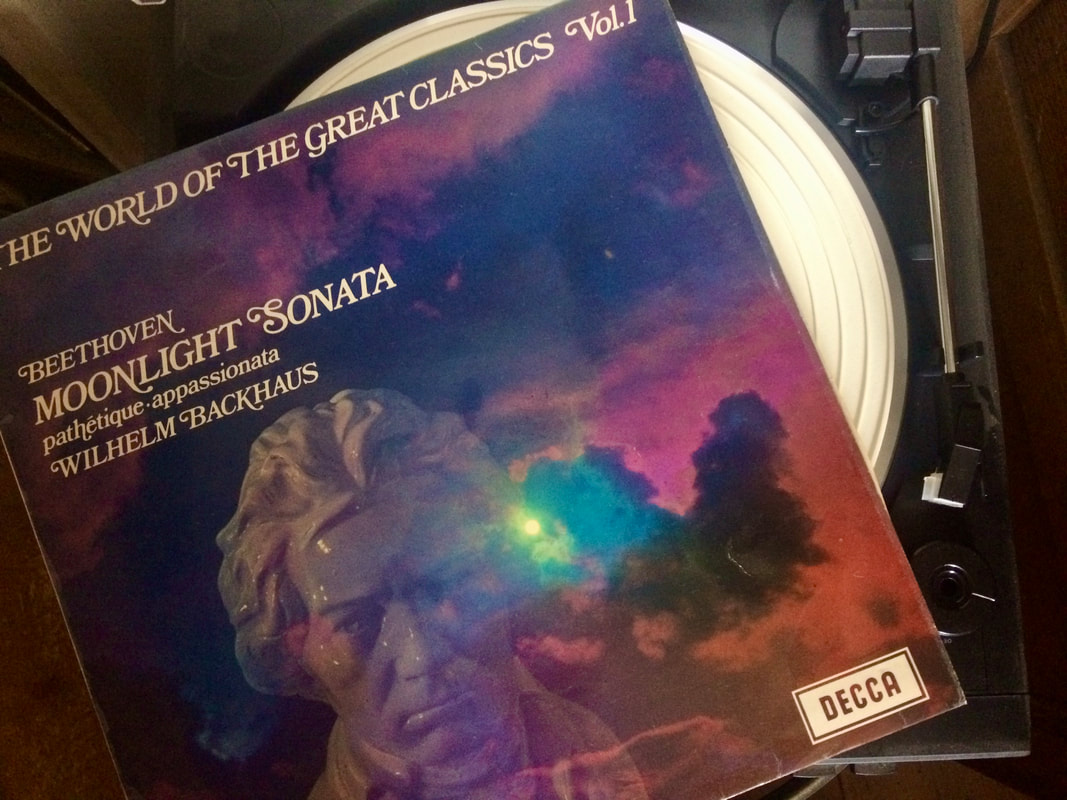

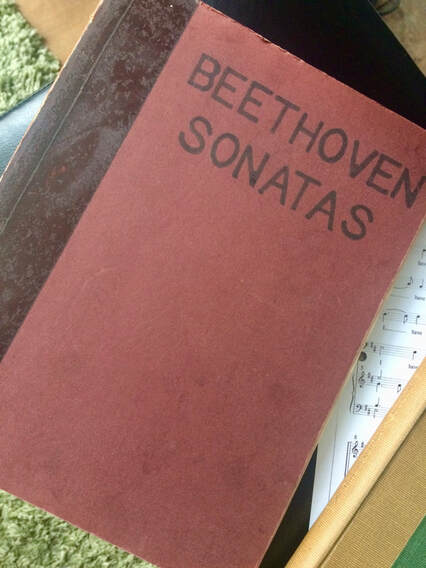

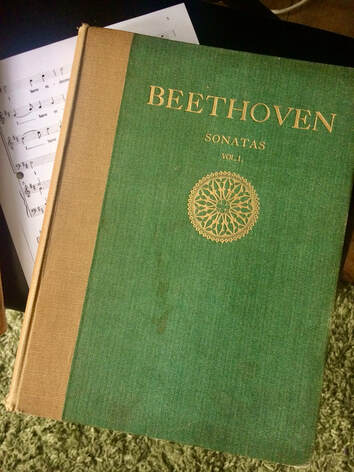

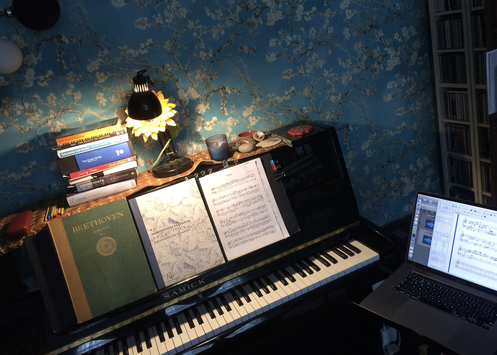

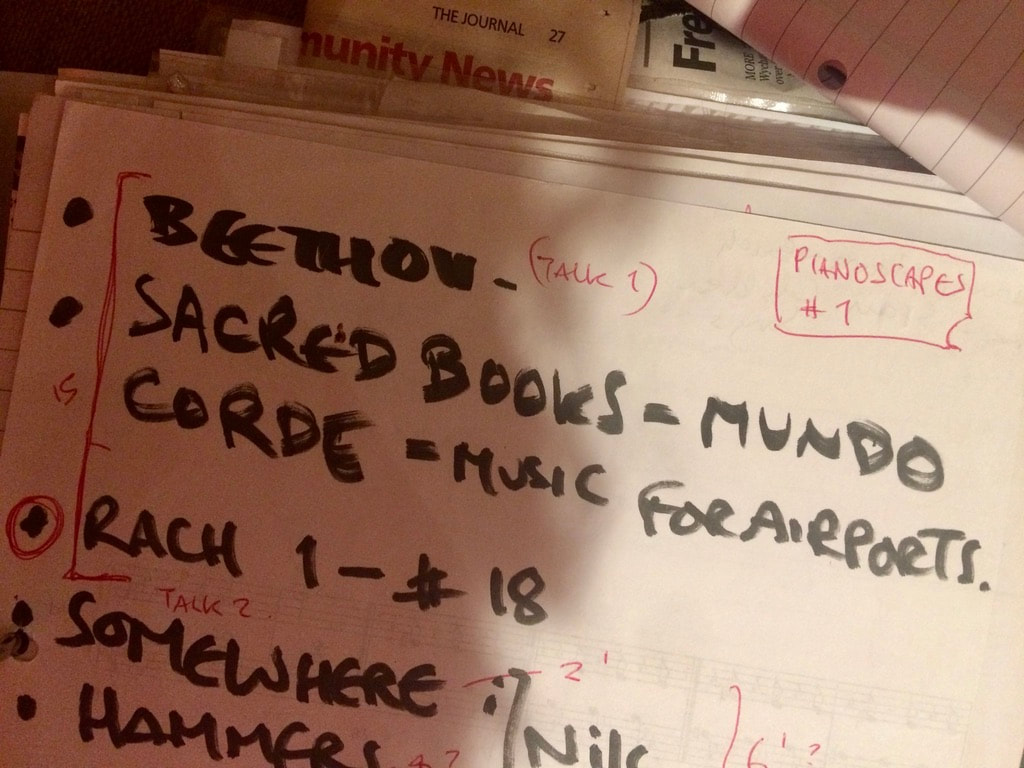

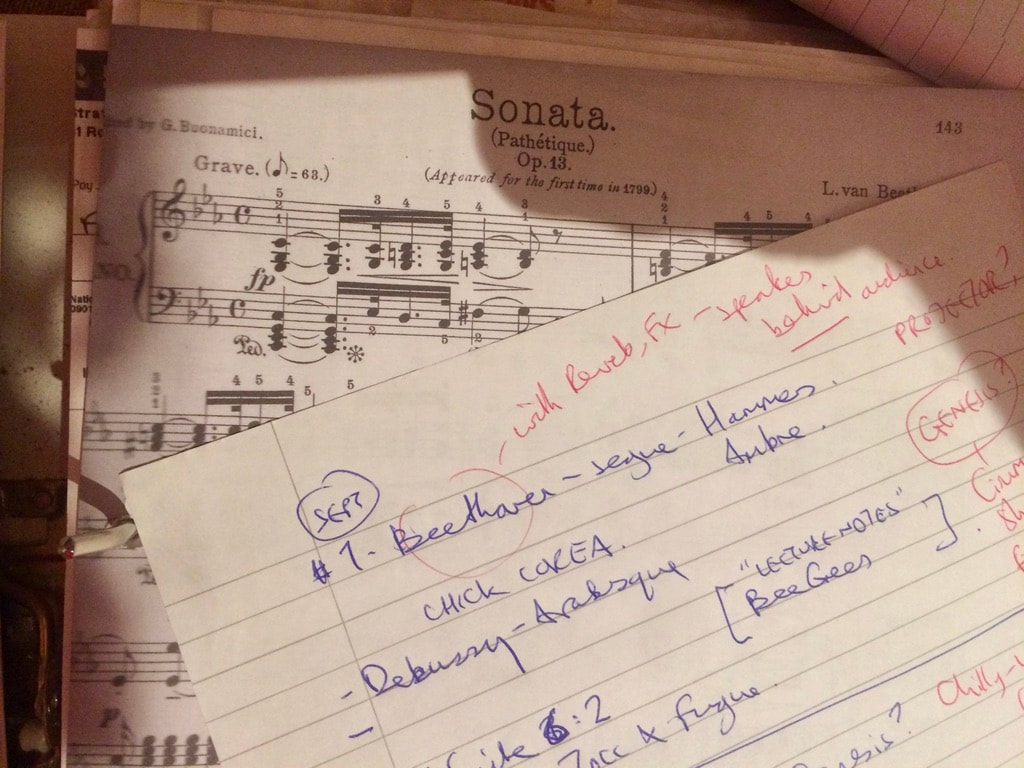

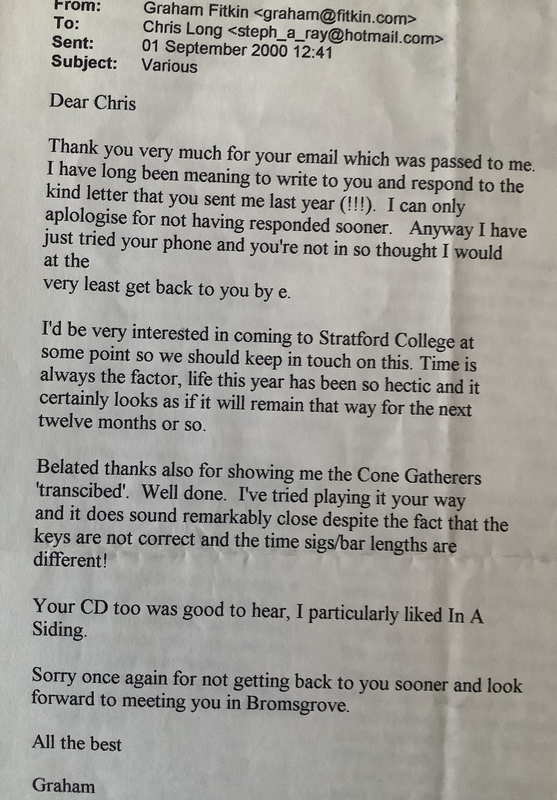

Pianoscapes no. 50 is fast approaching, and I'm playing music by Beethoven... Not something I would usually do. I first heard the music of Beethoven via his piano sonatas, on the album in the picture above - when I was a small child in the 1970s - at some point my parents thought it a good idea to own a Beethoven piano sonata album. Why, I wonder? I dunno, but the music was a totally immersive experience for my young and hungry imagination - it was overflowing with moods, ideas and energy. What is this?? And then, as an older child, probably in early teens - 1980s now - trying to play some of that same music. I think it was my sister that brought this book of the sonatas into the house; an old book, bound at the spine with what looked like packing tape and with home-made stencilling on the cover... The excitement of being able to read the music, and to make it happen for real, live - the 'Moonlight'! The 'Pathetique'! And later, when another (different) album of Beethoven piano sonatas appeared in my parents record collection, becoming acquainted with the 'Waldstein' sonata and trying to play that too. Wow! Powerful, exciting stuff.

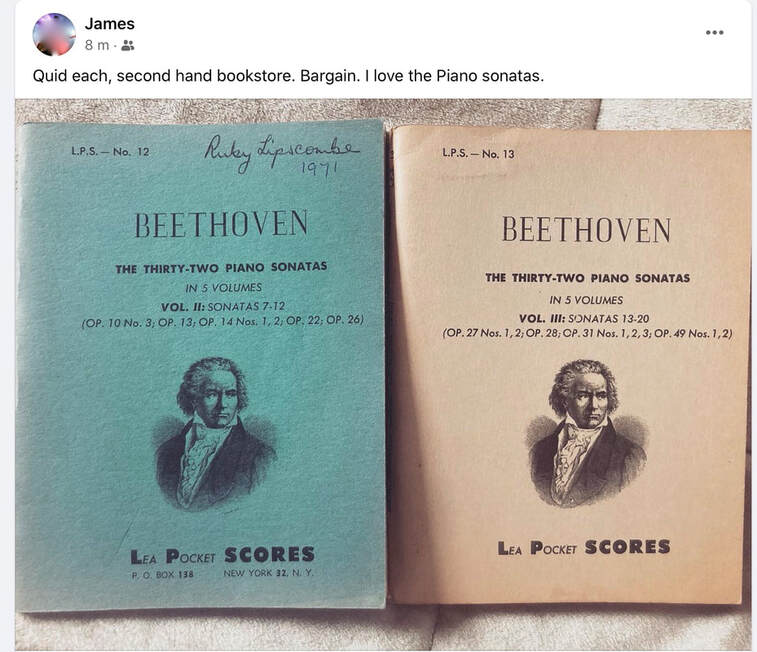

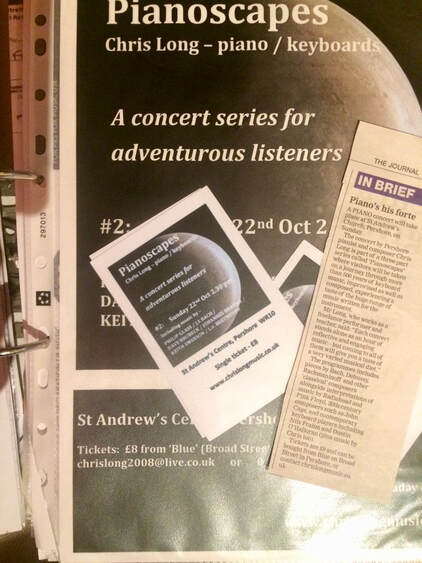

performed to an audience (c.1985? The only secondary school concert that I took part in, I think!). I guess it's just one of those pieces that every pianist has to play, and to know. And, goddammit, these sonatas are just beautiful. Whatever you think of 'classical music', this guy writes a damn good melody and knows how to create a drama. But the outer movements of the Pathetique are a bit more of a challenge, and take more work. Beethoven wrote it in 1798, when he was just 27 years old. Like the 'Moonlight' sonata, it's one of the most celebrated piano works in 'the canon', and the title refers to the due to the tragic and expressive nature of the music. It was written at a time when keyboard pieces needed to be interchangeable for either the (older instrument) harpsichord, or the (newfangled) pianoforte, and when you consider this music as a harpsichord piece - as I did only recently - it changes everything... It makes perfect sense, but it sure pulls the rug out from under you (well, it did me). Factor into this the bizarre but vaguely plausible ideas about tempo promoted by Wim Winters on Youtube (see his channel 'Authentic Sound'), and new approaches to the music of Beethoven present themselves. I had always avoided these sonatas as projects to get stuck into and really work at, being as they are the 'go to' pieces for aspiring virtuosi (ie. not me!), and rather 'obvious' choices; my preferences are for the paths less trodden, the more obscure music that needs playing because nobody else is playing it. But in August I decided to return to the 'Pathetique' and work on it with focus; to see it with new eyes and hear it with new ears; and to try and bring a more creative and interpretive sensibility to it than I would have previously allowed myself, being 'indoctrinated' as I was by those vinyl records of my childhood, into believing that there was only one way to approach this music. The volume above is the second set of the Beethoven sonatas that has come to me so far in my lifetime (I have Vol II as well as the pictured Vol I - 'the works'!). It's been good having it back on the music stand every day over the past few weeks. The usual signs and portents have been in evidence to support my activities in this Beethovenian direction. Two examples: (1) after playing through the sonata one evening in our accommodation in the west of Ireland, mid-August, the next day we went into a music shop in the locality... to be greeted by the sound of the 2nd movement of that same sonata, accompanied by the sound of waves on the shore - some new-age re-calibration of Ludvig's original.... (2) This, unprompted, on FaceAche, a few days ago, from an ex-colleague from the SUAC days... In conclusion - as a result of all this, I've been reappraising the piano sonatas of the late great LvB. As Alfred Brendel has written: “We pianists are fortunate to have the chance to follow the path of his 32 piano sonatas… Who else offers the range from comedy to tragedy, from the lightness of many of his variation works to the forces of nature that he not only unleashed but held in check? And which master managed, as Beethoven did in his late music, to weld together present, past and future, the sublime and the profane?”

|

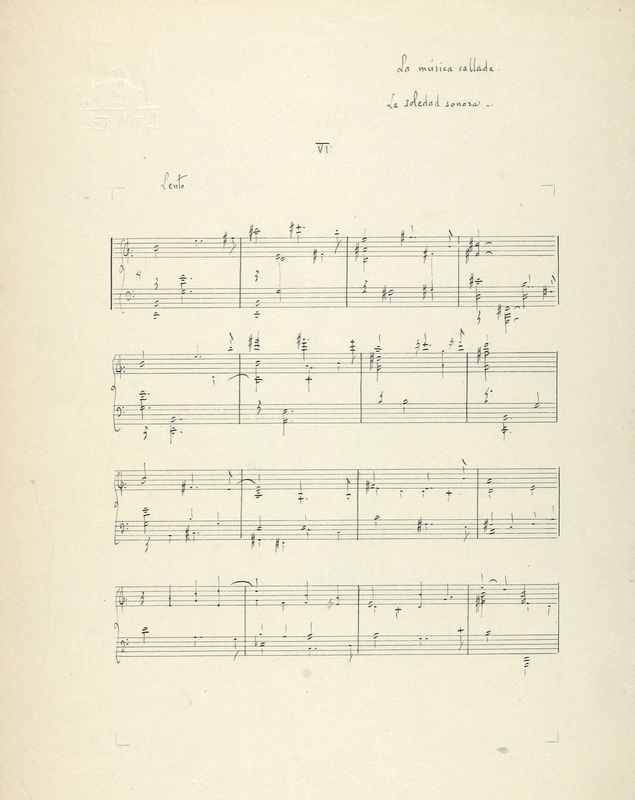

| The construction of the chords in Mompou's music seems derived from the overtones of bells, and to me feels designed to affect the alpha, theta and delta brain waves - brain activity associated with attention, focus, sleep and dreaming. These are more than pieces of music: they are magic spells and they change the listener who is able to submit to them. I hope the audience will go back to the music and hear it again, and again, maybe listening to performances by different pianists: the more you get inside these pieces, the more the language speaks to you. I also enjoyed the balance of notated music and improvisation that I had planned into the design of the overall concert: I was able to move between 'reader of the notation' - bringing what poetry I could to the dots on the page - to 'free-channelling', doing my best to enter a state whereby improvised music could speak through my playing. Moving between these states is a great discipline that I relish working on. |

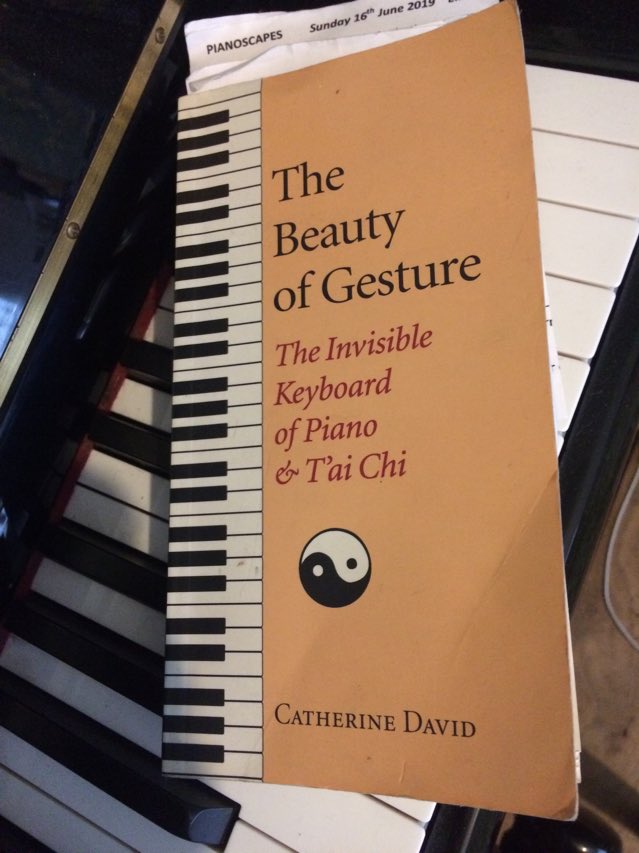

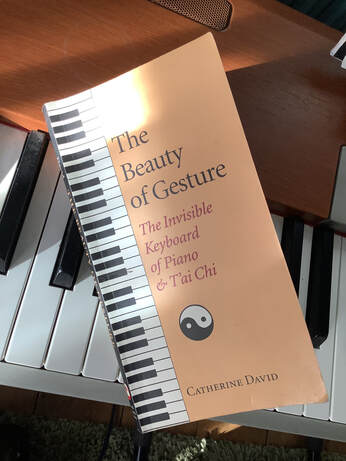

| In her book 'The Beauty of Gesture: The Invisible Keyboard of Piano & T'ai Chi', Catherine David states "The art of playing the piano could be defined as an attempt to touch music." This is a very neat and accurate summation, in my opinion. Whether 'reading the dots' written by others, or trying to subjugate the ego to allow 'inspired' improvisation of our own to happen - we are always aspiring to 'touch music'. It's why we work on technique - the physical skills required to play the instrument - and why we eat, drink and sleep music through our listening, developing a reflective and thinking ('mindful') approach to our musicianship. |

And if and when we are fortunate enough to 'touch music', then how lucky we are! "Music doesn't come in a gift parcel", writes Catherine David at the end of chapter 2: "It is the mirage of the quest." She writes eloquently about the process of work on technique, the meaning of 'practice' and the goal of 'touching music', in the 2 chapters that I've included below - well worth a read for all who aspire to develop as musicians.

And finally from me, a quote from Michael Pisaro, in his liner notes for James Rushford's recording of 'Musica Callada'. Perhaps if we were to touch music too deeply we would, as mere mortals, be burnt up. Perhaps the best that we can do is keep striving, and maybe we come close, and that's enough... Discuss!

"Notes wander in the pale light, seeking their place in the melody and the slats on the floor. They are hesitant, reluctant to assert themselves, don’t want to be observed too closely... We spy on the music, listen indirectly, around the chords, to the silences between them... Looking directly at the heart of the music would be like looking at the sun"

Chris Long, Monday 21st February 2022

And finally from me, a quote from Michael Pisaro, in his liner notes for James Rushford's recording of 'Musica Callada'. Perhaps if we were to touch music too deeply we would, as mere mortals, be burnt up. Perhaps the best that we can do is keep striving, and maybe we come close, and that's enough... Discuss!

"Notes wander in the pale light, seeking their place in the melody and the slats on the floor. They are hesitant, reluctant to assert themselves, don’t want to be observed too closely... We spy on the music, listen indirectly, around the chords, to the silences between them... Looking directly at the heart of the music would be like looking at the sun"

Chris Long, Monday 21st February 2022

From 'The Beauty of Gesture':

Increasingly, I'm hearing the bells in the music.

The bells are there from the outset.

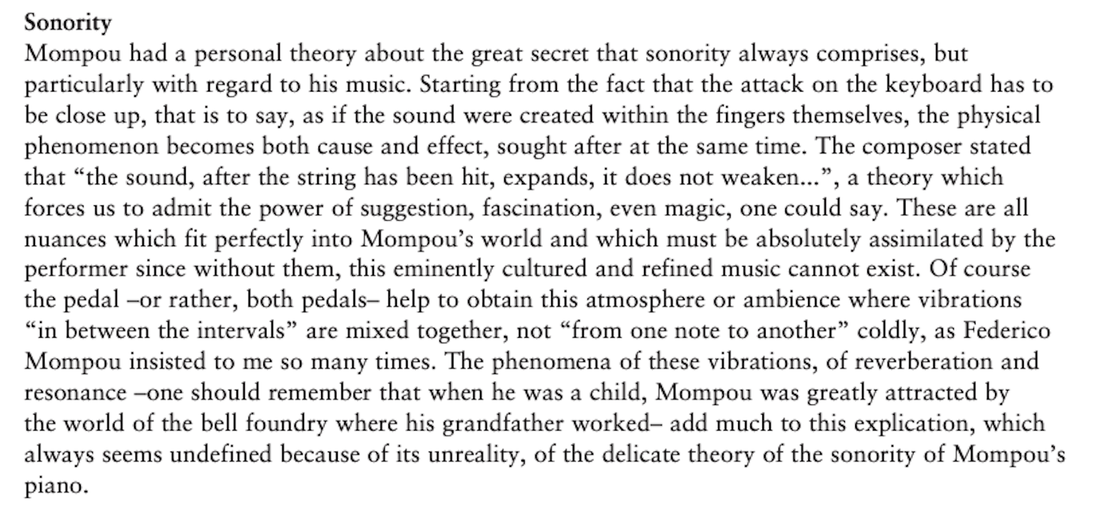

The first piece, 'Angelico', begins with a symmetrical 'tone formation' - A & B, D& E - two major seconds separated by a minor third - and it is out of this that a melody emerges. The 3 notes below the melody chime like a bell, hanging in space, as the melody floats above.

The first piece, 'Angelico', begins with a symmetrical 'tone formation' - A & B, D& E - two major seconds separated by a minor third - and it is out of this that a melody emerges. The 3 notes below the melody chime like a bell, hanging in space, as the melody floats above.

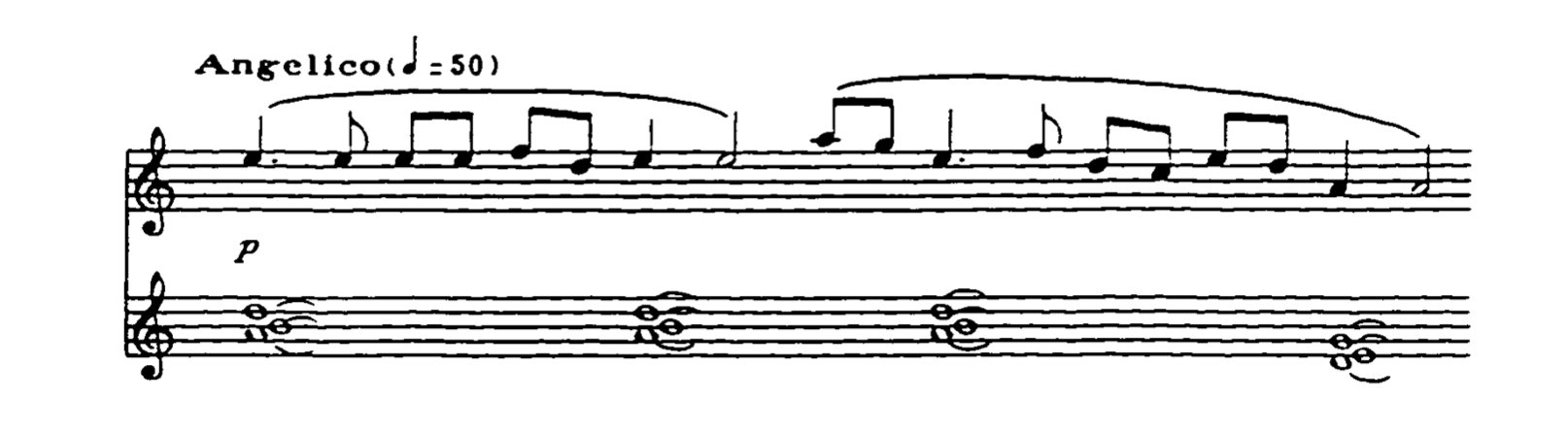

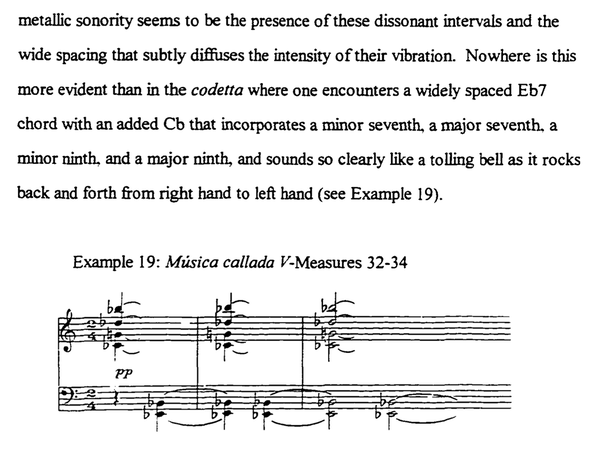

Then follow three quite different pieces; as Eric Daub mentions in his excellent analysis of Musica Callada, "While the presence of contrasts within the individual pieces is usually rather subtle, the contrasts encountered between the pieces can be quite pronounced". When we reach #5 we are "taken into a musical world that is concerned with the evocative power of a single sonority".

I was listening to this piece while driving the other day, and the performance (by James Rushford) struck me (pun intended?) in a way it never had before. These are clearly bells; I'd never heard the chords in this particular piece as bells before, after 30 years of knowing this music - and the harmonies Mompou has written must have been derived from a study of the actual overtones of bells. The dissonances arise from major sevenths and minor ninths...

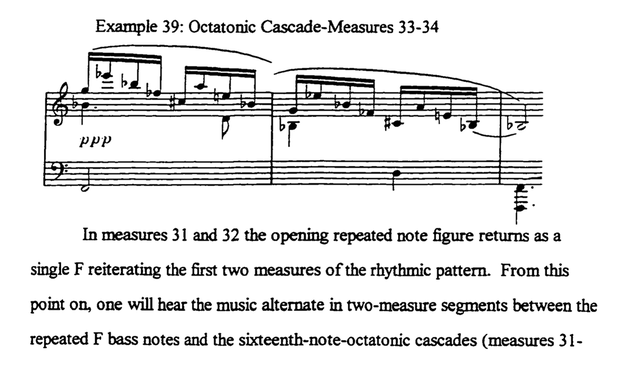

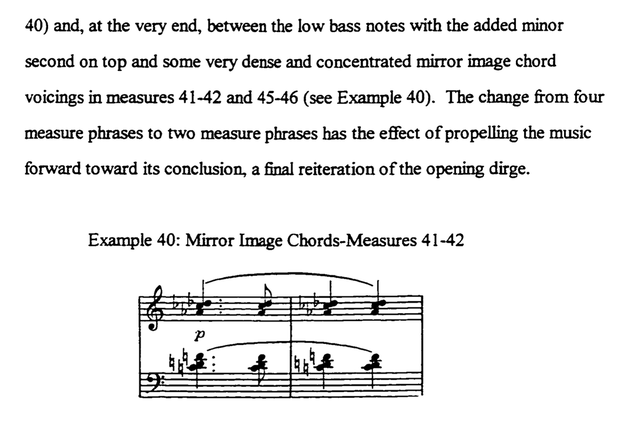

The bells continue to underpin the music as we go further into Book 1, and then into Book 2. Nos. 11 and 12 are both very bell-like, to my ears: 11 has a bright carillon-like theme at the opening and closing, like an announcement; no 12 has "colourfully dissonant metallic sonorities" [Eric Baum] which move into passages using the octatonic scale. The use of this scale to produce magical and mystical effects has precedents in 20th C music, most notably in the music of Scriabin, and Stravinsky.

In his blog "The Departing Landscape', Steven D Foster describes 'Musica Callada' as a sacred music:

"I consider Musica Callada to be a sacred work of art, and there are several ways in which I have become certain of this fact. First of all, when I listen to Mompou's music I become entranced by its sweet melodies, its constant other-worldly ringing of bells, its palpable and sensitive use of silent spaces, and its elegant dissonances which are pervaded with transcendent charm. All this is to say that the music absorbs my attention, opens my heart and transports me to beautiful unknown worlds. "

He goes on -

"The third chapter of Wilfred Mellers' book Le Jardin Retrouve, The Music of Frederic Mompou is devoted to bells. He begins the chapter with some interesting history:

"The musical synonym for 'pre-consciousness" is the bell. Both real bells (inverted cups, usually of metal, hit with an attached clapper or externally activated hammer) and crotals (hollowed gourd-like objects with a free body, such as pea or pebble, inserted) may be said to belong to God in that they reveal the acoustical properties of Nature. Some 26,000 years before Christ the Chinese Emperor Chuan Hao 'struck the bell and called the attention of the people, so that he could teach them righteousness'; the teaching came after the submission to Nature. Chinese bells were decorated with dragons and other fabulous creatures least demons should threaten the transcendental power whereby bells sustained the Universal Harmony; without truly resonating bells the universe might collapse. Most ancient oriental cultures regarded bells as agents and activators of magic. Hindus found in them the circle, hemisphere and lotus basic to their cosmology . . .

"Vladimir Jankelevitch writes about the resounding bells in Mompou's Musica Callada in an essay "Mompou's Message" which can be found--in English translation!--in the booklet that comes with the 4CD set entitled Mompou : Complete Piano Works on the Brilliant Classics label. It is an important essay; here are some excerpts taken from it:

"Mompou's piano pieces constantly allude to bronze . . . the bronze of bells vibrates and resounds in the musical space where Mompou's compositions are heard . . . especially in Musica Callada (Silent Music): here one hears seraphic bells which chime softly between heaven and earth.

"It is hard to decide what to admire most in these wonderful piano pieces where the pressure of each finger has been subtly considered. "Profundo" (deeply): this indication for performance enamels all Mompou's works, as if wanting to penetrate in the deepest part of the soul; the sonorities are sedative, calming, serious, vehement, or sometimes mysteriously hammered out, and often, they are soft and captivating. The sweet melodies create a sonorous light in the depth. Between the airy notes and the deep ones, an intermediate voice stands out, which sketches the internal song of harmony . . .

"In the whole work the musician lets another voice, originating in the "resonating" strings, sing . . . and this second voice, this secret voice, this "internal voice" addresses us as if it were the voice of the soul. This unspoken music gives the music we hear its vibrant fullness. From all this comes a sonority which is at the same time hidden and delicately articulated, a fleeting sonority, and yet, luminous, evasive but unattached . . . [for] distance and space underlie all the impressions and images in Mompou . . .

"It seems right to me that, over the years, the mystic silence represented more and more for Federico Mompou the intimacy of the internal state towards which he always moved. The serenity he always searched for is even more static than withdrawn. The existence of his aestheticism was confirmed . . . above all in the four books of Musica Callada. . . . What Mompou wants is the search for "sonorous solitude"; to reach the intangible point where music becomes the very voice of silence, where silence itself becomes music. . . . Mompou aspired to let the voice of the pure soul sing, the soul alone, the soul itself in itself . . .

Vladimir Jankelevitch, "Mompou's Message" published in the Brilliant Classics booklet. (my underlines)"

| Look out toward the last glow of sunlight, and look in toward the endless sky. Drink the nectar of the petals of your heart and let wave upon wave sweep through your body. What glory is in the ocean! Listen-- The sound of conches! The sound of bells! Kabir says, "O brother, listen! The Lord of all plays his song within you." Kabir | Let us be silent So that the Giver of Speech may speak. Let us be silent So we can hear Him calling us secretly in the night. Rumi All Worlds come out of the sound OM. Gurumayi Chidvilasananda |

| " What is he playing? —It's a fragment of Mompou's Silent Music. —That's what I call a good ear. —That's what I call using Mompou as background music while I work and having read Jankelevitch's essay on Mompou, Le message de Mompou. Jankelevitch is a philosopher at the Sorbonne. Look at the apparent independence of the fingers, feel the sensation of clarity in each note. You have to go back to Chopin to find such rare magic at the piano..." |

The written extract above is from "The Pianist", a novel by Manuel Vazquez Montalban. It is true that the sonority and clarity - and poetry - of Chopin's music was of central importance to Federico Mompou; indeed, Mompou wrote his own set of variations on one of his namesake's melodies. With every session of playing Musica Callada, I'm furthering my understanding that poetry, sonority and rubato are cornerstones of the language of both of these composers.

Wilhelm von Lenz, who studied with both Liszt and Chopin, believed rubato formed the very heart of Chopin’s playing: “He would say, ‘A piece lasts for, say, five minutes, only in that it occupies this time for its overall performance; internal details are another matter. And there you have rubato.’”

“Rubato” may be written in only nine of Chopin’s manuscripts - only nine! -but is essential to nearly all of them.

“Look at these trees,” Franz Liszt said, “the wind plays in the leaves, stirs up life among them, the tree remains the same, that is Chopinesque rubato.”

With Mompou, where does the borrowing of time begin and end? The composer... [please take over, Mr Antonio Iglesias - ]

Wilhelm von Lenz, who studied with both Liszt and Chopin, believed rubato formed the very heart of Chopin’s playing: “He would say, ‘A piece lasts for, say, five minutes, only in that it occupies this time for its overall performance; internal details are another matter. And there you have rubato.’”

“Rubato” may be written in only nine of Chopin’s manuscripts - only nine! -but is essential to nearly all of them.

“Look at these trees,” Franz Liszt said, “the wind plays in the leaves, stirs up life among them, the tree remains the same, that is Chopinesque rubato.”

With Mompou, where does the borrowing of time begin and end? The composer... [please take over, Mr Antonio Iglesias - ]

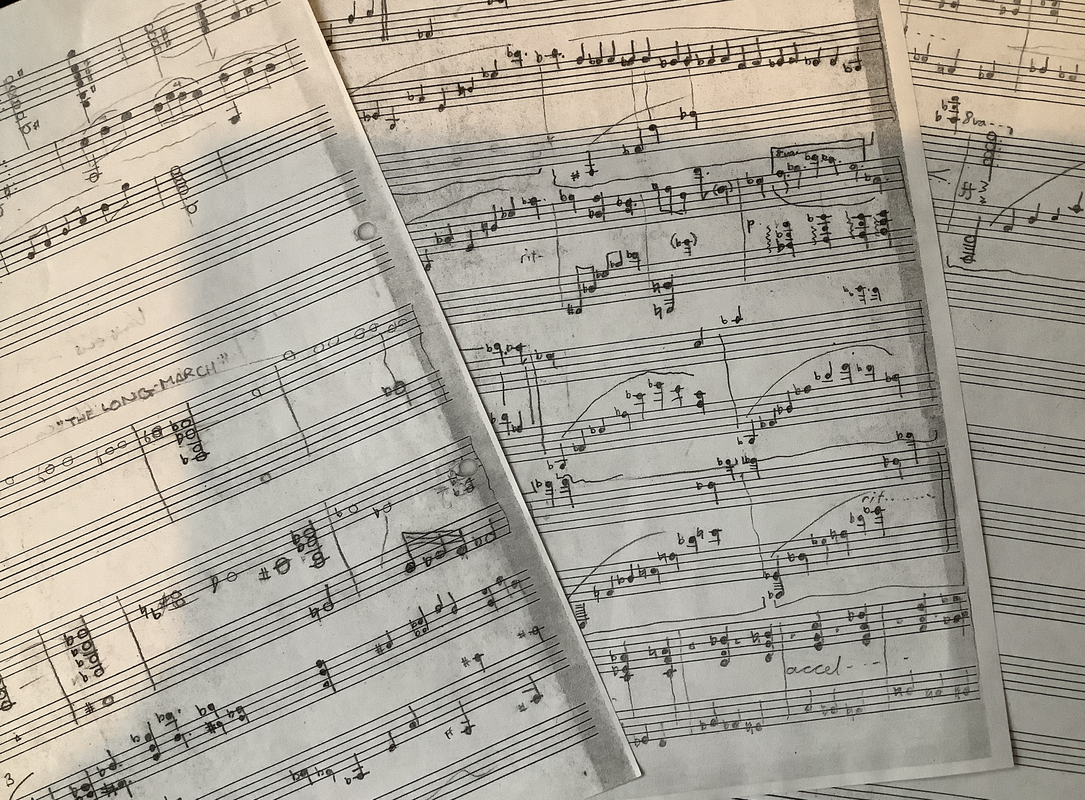

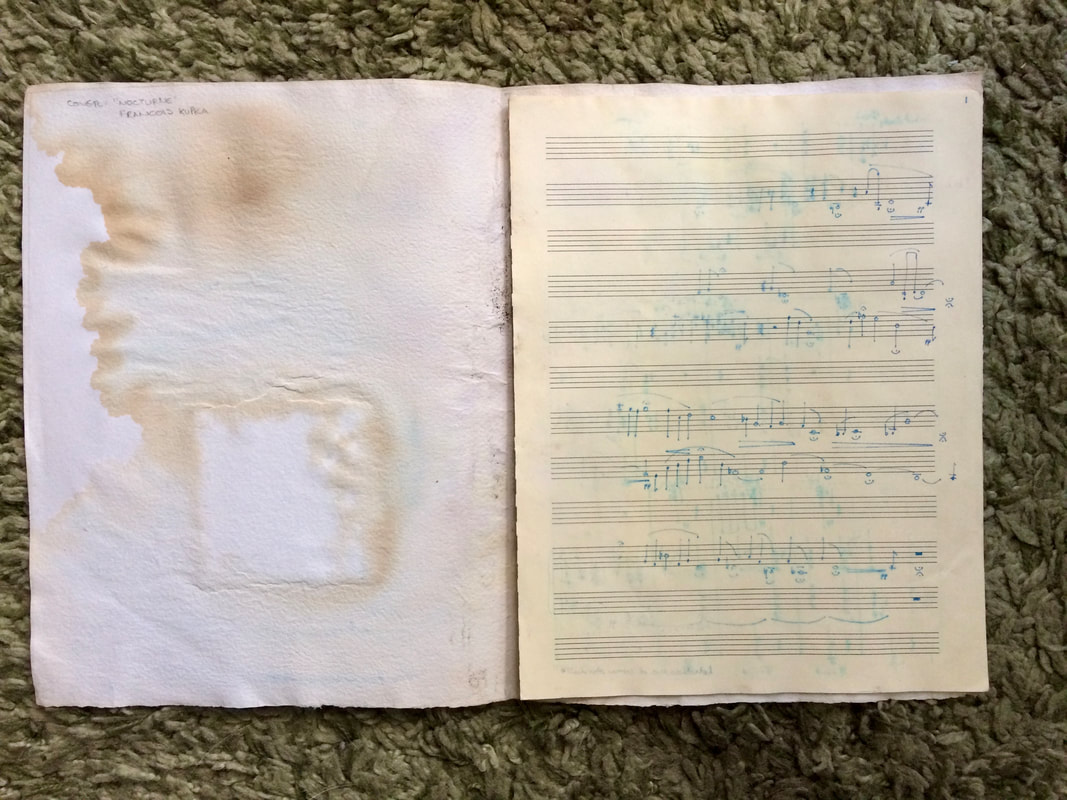

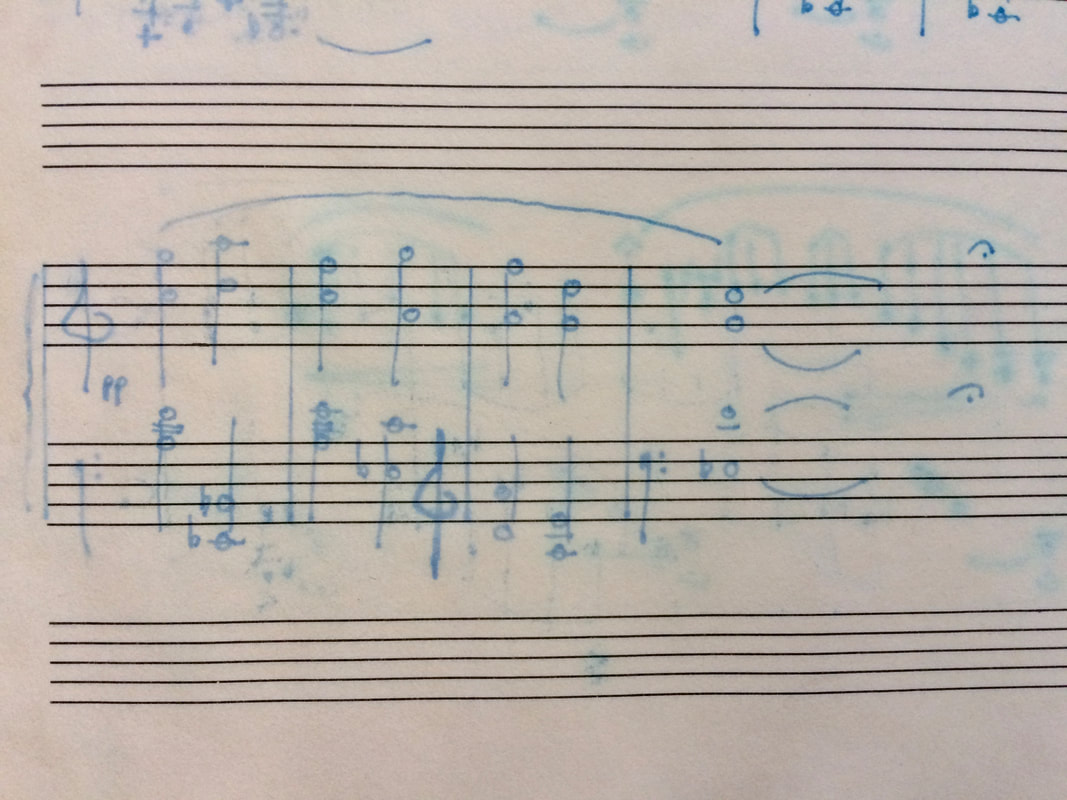

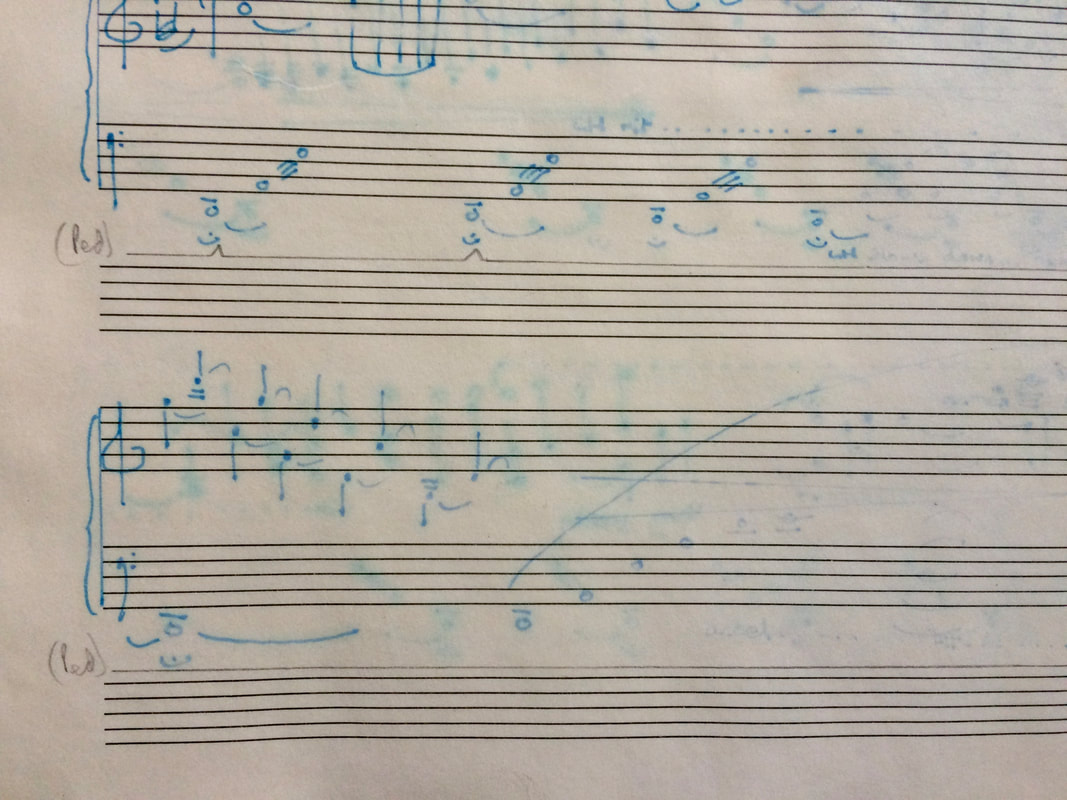

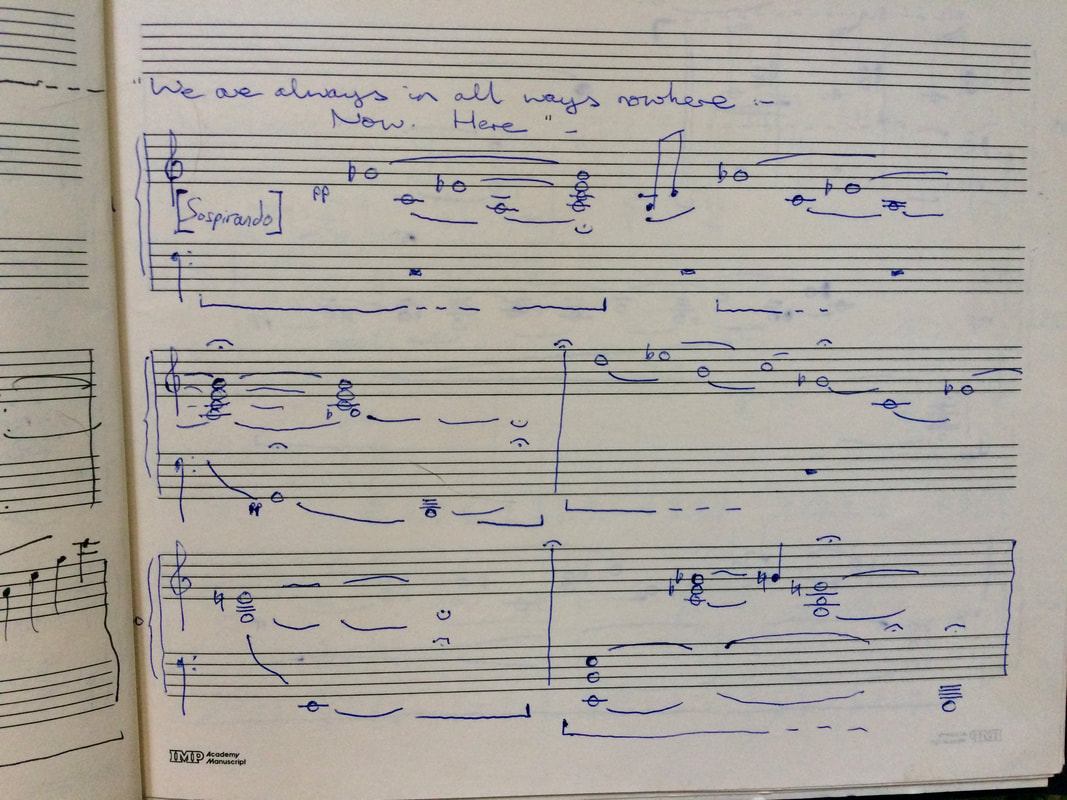

| The images above and below are from a composition of mine composed in 1988: 'Primordial'. Clearly Mompou was in the ear and mind of the 17-year old that penned this work. Between 2008 and 2013 most of my early scores suffered water-damage and now those open-ended drifts of notes are even more elusive, as they evaporate into blurs on the page... Time & sound dissolve. |

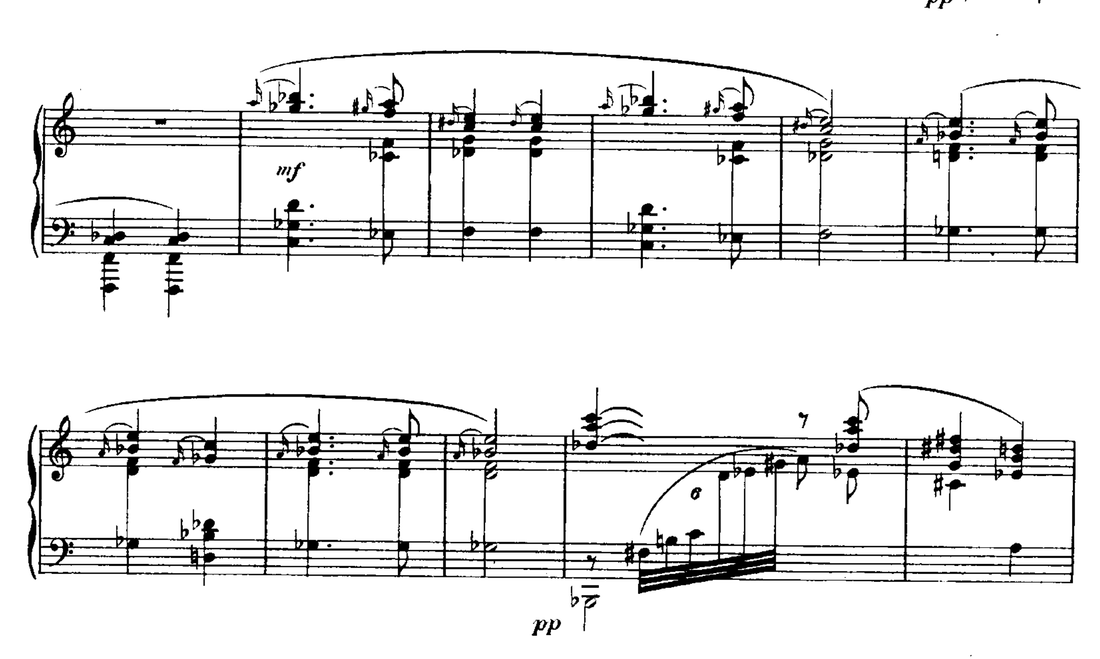

This evening, in my work on Mompou's music I've been particularly relishing the chords in Book 2: there are many different characters to be found here. In no 12, the harmonies bring the music of Olivier Messiaen to my mind:

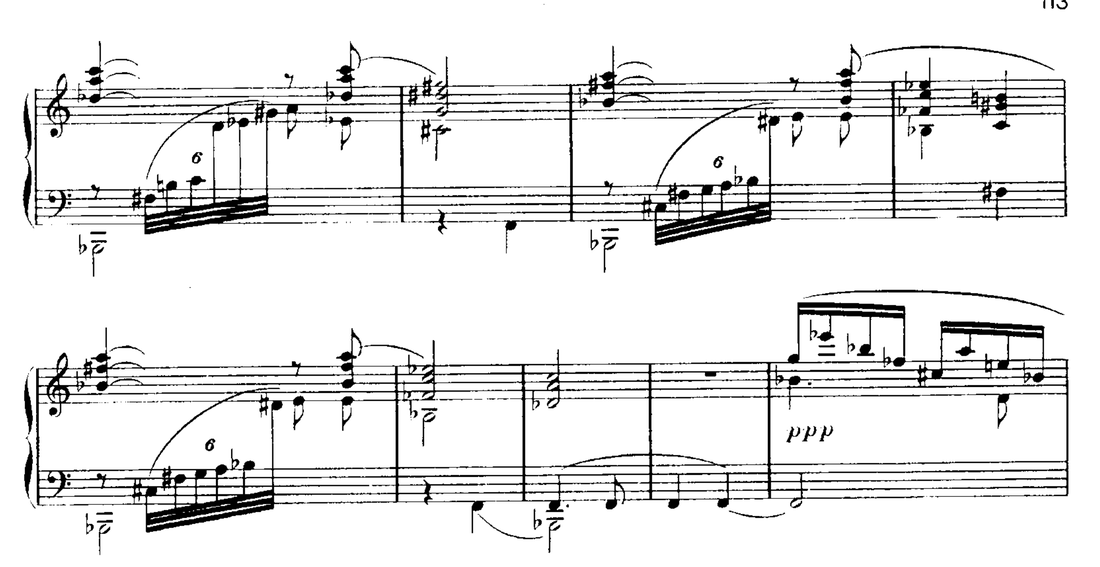

And in no.16, Bill Evans makes an appearance -

I'll hand back to Mr Iglesias for the final words tonight -

Signing off -

Chris

6 Feb 2022

Musica Callada Books 1 & 2 - to be performed in 'Pianoscapes' on February 20th.

See 'Pianoscapes' page on this website.

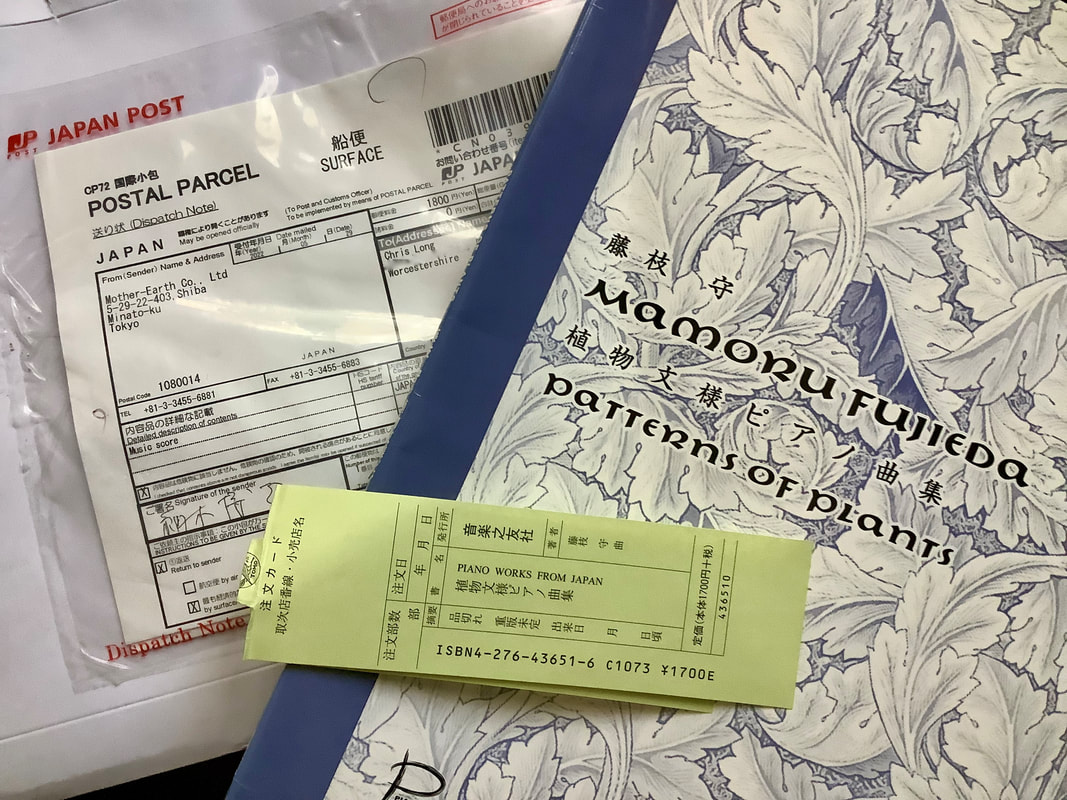

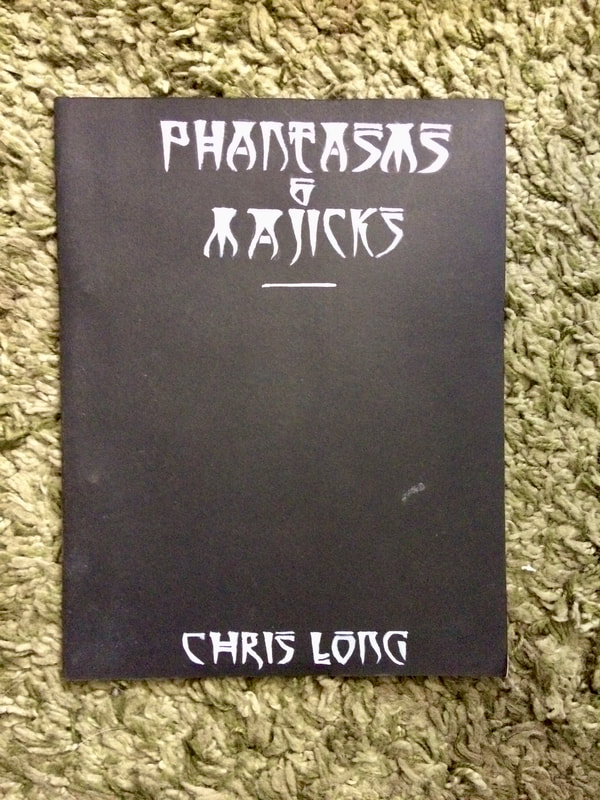

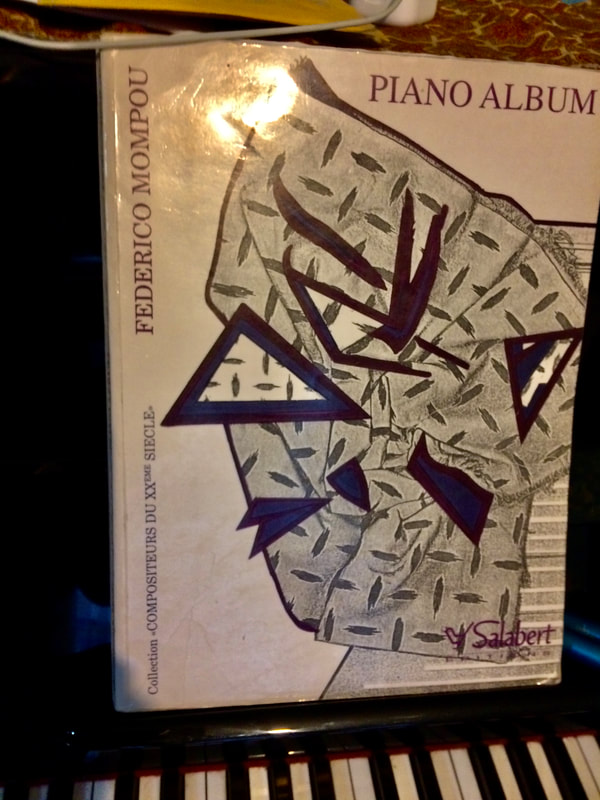

| As the government goes 'into meltdown', I'm enjoying losing (or rather, finding) myself in the pages of 'Musica Callada'. As 2021 turned into 2022 I made the commitment to a performance of all 4 books of this mysterious work by Catalan composer Federico Mompou, as my first ‘major’ performance project of the year - the idea had been forming in my mind during the second half of 2021, and moved closer as I discovered the recording by James Rushford, paired with his own very abstract work ‘See The Welter”. I've know 'Musica Callada' for decades, but this discovery via Bandcamp was revelatory: I was struck by James Rushford's sleeve notes and by his profound interpretation - and as a result, finally, to use a phrase used this week by Johnson - untruthfully in his case, of course - "I get it". Mr Mompou and I go back a long way: I’ve been intrigued by his music since I was a hairy hippy piano student in the 1980’s. My teacher Mary introduced me to the world of Satie and stave-free scores, and Mompou followed hot on Satie's heels – ‘Cants Magics’ and ‘Cancion y Danza 6’ are the pieces that I remember Mary introducing me to. The former of these was the inspiration for a lot of my own compositional ‘juvenalia’ – suites of quasi-mystical musical noodlings, notated with ‘hanging’ ties, ‘space-time notation, and a spurning of barlines. Titles like “Phantasms & Majicks”, “Soul Cakes”, “Biomechanoid”… And then, to University... In my second year, between studies, I had a part-time gig working as a ballet-school accompanist in Wimbledon (Margaret Fleming School of Dance), and later in Kingston for Ms Fleming's young protégé Christina Ross. Christina was studying down the road at the Roehampton Institute, and asked me to put some music together for a choreography assignment that she had to create and perform. I ended up returning to Mompou's Cants Magics – and it turned out to be great music to dance to. I dimly recall the performance: I hope my playing did justice to Christina's work, and that I wasn’t too nervous (or dressed too ridiculously). Around this time - early 90's - on one of my many trips Up To Town, and to Foyles at Charing Cross Road, Covent Garden in particular; on the top floor, where I acquired my Giacinto Scelsi scores, my score of Arvo Part’s ‘Tabula Rasa’ and my copy of Shostakovich’s Preludes & Fugues (book 1); that’s where I got my copy of Mompou’s ‘Piano Album’, an Editions Salabert publication. And it’s here, I think, that I first encountered ‘Musica Callada’. I’ve been playing Book 1 since that time - c. thirty years now... In addition, I've played a lot of Mompou's other music - Cants Magics, Impresions Intimas, Preludes... and during that time I’ve looked through books 2-4 of Musica Callada, enjoying the change in typeface in the printed music, and the typically Mompou-ian (?) appearance of the musical shapes on the page. Around 1994 I was given a CD of Herbert Henck’s interpretation of all 4 books, but... ... Somehow Books 2-4 never seemed to engage me enough for me to get stuck into them; maybe there was too much other music to play. I guess the time wasn't right. Last year, on hearing James Rushford’s interpretation, suddenly the music connects with me. I hear it with fresh ears; the time is right now for this music to speak to me and I, in return, to be a voice for it to be heard. |

And as I learn more about each of the 28 pieces by playing and researching - making time for the music, listening deeply - the journey into Mompou's language becomes increasingly fascinating. I'll be posting here, hopefully regularly, offering glimpses into this process.

Stay tuned!

Signing off -

Chris

4 Feb 2022

Musica Callada Books 1 & 2 - to be performed in 'Pianoscapes' on February 20th.

See 'Pianoscapes' page on this website.

Stay tuned!

Signing off -

Chris

4 Feb 2022

Musica Callada Books 1 & 2 - to be performed in 'Pianoscapes' on February 20th.

See 'Pianoscapes' page on this website.

Can it be true that my last blog was 4 years ago?

If so, another one is long overdue. Strap yerself in...

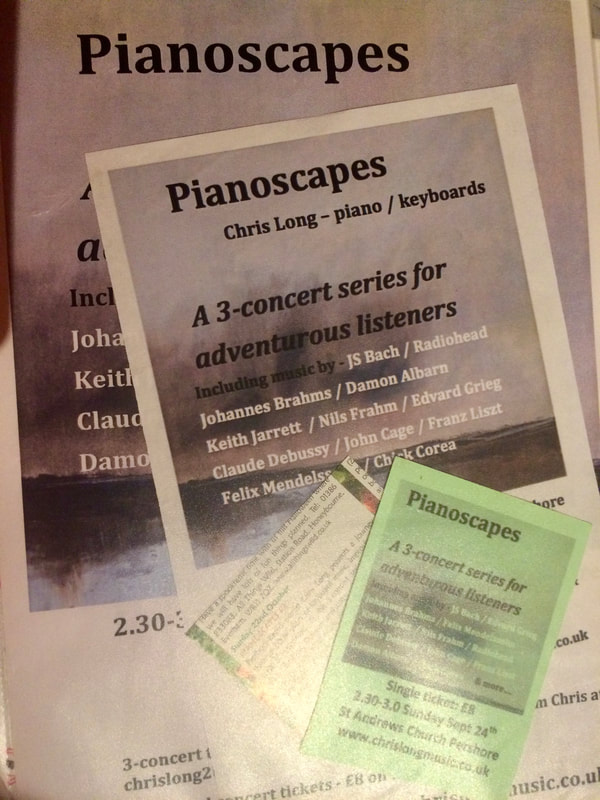

This time I’m writing a few words ahead of my next performance, which is this coming Sunday – ‘Pianoscapes’ on June 28th. I’ll be explaining some of the reasons for the musical choices, but there are going to be various threads to this, and a number of inescapable but necessary diversions. Bear with me…

I’m starting with this: it seems to me that, as we emerge from ‘Lockdown’ into some kind of ‘post-Lockdown middle ground’, that the unresolved sounds of the whole-tone scale, and the ‘augmented’ tonalities that it generates, seem to be coming up as the ‘Music of the Lockdown’ in my world… That seems very appropriate: time is suspended; there’s no obvious direction; everything (except for nature) is in a kind of stasis… this scale, and the chords that it generates, encapsulate this ennui very well….

In the first ‘Zoom’ lessons with my student George – back at the end of March and into early April - we’d been working on, amongst other things, Liszt’s ‘Consolation no.3’. Hot on the heels of this, and to round out his knowledge of Liszt (ie. not just as the virtuoso composer and performer of the High Romantic Age, but also, in his old age, as a pioneer of ‘expanding tonality’ at the end of the 19thC), I had George have a look at ‘Nuages Gris’. This short piece of music, composed in 1881, dwells almost exclusively in the strange land of ‘augmented tonality’ – as do most of Liszt’s late pieces – and it’s a murky place of unresolved and mysterious chord progressions, leading the listener into existential places…

Off the back of this – and as a way of connecting all of this back to jazz (we’d also been looking at Jacob Collier’s arrangements, and extended harmonies of various kinds) - I set him the task of composing a piece for piano that only uses augmented chords and sus4 chords, to stretch his ears and cultivate a feeling for unresolving harmony…

Then, as we moved out of April and through May – out of nowhere? – came an online performance of ‘Vexations’ [Erik Satie, composed 1893]. I can’t remember how it happened but I became aware of composer and old-time-COMA (Contemporary Music For Amateurs)-buddy Kathy Hinde organising a performance of this infamous piece: a short 42-beat sequence of augmented triads, to be repeated 840 times… ‘very slowly’… something that can take anywhere between 15 and 20+ hours.

This realisation of ‘Vexations’ was comprised of 840 different ‘single passes’ at the 42-beat sequence, recorded by different musicians and submitted to Kathy; these were then rotated using a piece of randomising software until 840 iterations had passed – which did take over 24 hours (I think)...

I’d taken part in a live realisation of this piece a few years back (2016), as part of the Cheltenham Music Festival. I’d even clocked in an appearance on BBC’s Midlands Today as a result (I was the performer that started the proceedings). It’s a tricky one to prepare for: you can work on the music itself (the score is written using double flats and double sharps to make it deliberately tricky to play), but perhaps you’re unlikely to play it over and over ‘in preparation’ for the ordeal that you will be called upon to undertake... My ‘Vexations Baptism of Fire’ was actually OK: I think I did about 20-25 mins on this occasion, and very much enjoyed the experience… the music has the effect of ‘warping time’ and really focusing the mind.

But as May morphed into June - in fact, on May 31st - Kathy emailed me to let me know that a live solo performance of ‘Vexations’ had begun in Berlin that very day, at 2pm UK time. Pianist Igor Levit (I’d been aware of his recent album ‘Life’) was well underway when I tuned it c.6pm and became immediately fascinated by this (rather voyeuristic) process of self-immolation. His ‘performance’ was to become increasingly nightmarish to witness as his 15-hour ordeal wore on…. the awful reality of the repetition of days, the isolation, the prison that lockdown has the potential to be, was writ large and brutal in this epic struggle of mental strength, perseverance, physical stamina and sheer bloody-mindedness (the link below is an 11-hour extract from the 15-hour performance)...

But – I haven’t yet explained these ‘augmented’ tonalities.

Take a major triad and raise the fifth degree of the scale a semitone; you then have a symmetrical structure: 2 major thirds stacked up (1-3, 3-#5). It’s a chord that’s on the way to somewhere – you could call it a ‘passing chord’, which would usually connect 2 other chords – but when it’s used as a chord on its own terms, the resulting music hangs ambiguously and doesn’t resolve.

Or pick a note, any note, and ascend in intervals of a whole tone. You’ll be playing a whole tone scale, designated by Olivier Messiaen as no. 1 of the ‘modes of limited transposition’ (so-called because you can only transpose it once: up a semitone. If you transpose it again, the resulting set of notes are the same as the original set). This scale is familiar to most people as the musical cliché in a film context, suggesting water or a dream sequence (and usually played on a harp!).

If you build triads out of a whole tone scale, you generate a sequence of augmented triads.

The scale and its chords have appeared in the music of Debussy and other Impressionist composers – it turns out that the current Grade 8 piano syllabus that George is working on contains ‘Voiles’ from Debussy’s 1st Book of Preludes – one of the quintessential wholetone pieces in the piano repertoire.

And George also wanted to work on some music by Stevie Wonder – initially, ‘Isn’t She Lovely’, which has become a bit of a jazz-standard-showcase; but, it then occurred to me, ‘You Are the Sunshine of My Life’ begins with a rising set of augmented chords…

And then there’s Keith Emerson. A cornerstone of his musical fingerprint is the use of quartal harmonies, sus4-type shapes, and augmented tonalities. Side 2 of the 1st Emerson, Lake & Palmer album opens with 'The Three Fates’, a fiendish piece which is almost exclusively built from these elements, and one that I've been working on since I found a transcription of it at least 10 years ago - and, (co?)incidentally, had chosen to start chipping away at again, just before Lockdown began... So back it came, back onto the music stand during May and June.

So, at last, we get there. I’m going to start Sunday’s concert with 'The Three Fates', music that has accompanied me from pretty much the beginning of my musical odyssey (my brother was given the ELP album for his 12th birthday, when I was an impressionable 8 year-old, and it became an obsession for me from that point). 'The Three Fates' themselves come from Ancient Greek mythology: Clotho ("spinner"), Lachesis ("allotter") and Atropos ("the unturnable", a metaphor for death). They controlled the mother thread of life of every mortal from birth to death. The music is at turns dramatic, rhapsodic, and frantic: 'Clotho', for organ, alternates forte passages based on gritty suspended chords, with florid RH episodes on the flute stop; 'Lachesis' is a relentless augmented-tonality solo piano drama; 'Atropos' is a wholetone-based driving ostinato slap-in-the face, ending with the music dragging us down into Hades itself.

As is always the case, a 'Piansoscapes' programme evolves in tandem with events that occur leading up to it - sometimes as late as on the day itself. This month there have been two deaths that have impinged on the evolution of the programme: firstly - and continuing the 'augmented tonality' theme - I'll be playing music by another Keith - Keith Tippett, another musical hero (and a Bristolian!) who passed away this month. Improvisation is at the core of his life's work: so finding a specific 'piece' to 'realise' isn't straightforward. fortunately, as part of an 'online memoriam' my neighbour Mr Fripp posted a song by his good lady, Toyah, which features a guest appearance by Mr Tippett: he’s playing a 2-chord vamp which uses minor-major7 chords – structures which contain within them our old (or new?) friend, the augmented triad… So I’ll be including that piece too, or at least an improvisation on Keith’s bit of it, as a homage to the man himself .

[incidentally – there’s a petition to have the Colston Hall in Bristol renamed as The Keith Tippett Centre’ – sign the petition here - www.change.org/p/bristolmusictrust-org-uk-renaming-colston-hall-to-the-keith-tippett-hall-centre?recruiter=22332670&utm]

And then there’s the music of Mr Fripp himself – in particular, ‘Fracture’ – another piece built almost exclusively from augmented chords and whole-tone materials. However, working this up will take time: notoriously ‘impossible to play’ (on guitar, at any rate!), I’ll be trying to get this ready for July’s 'Pianoscapes’… watch this space…!

CURIOSER & CURIOSER...

Leaving augmented tonalities aside now... phew… the other pieces I’ll be playing include a homage to actor Ian Holm (the other personage who is lately deceased) – he starred in ‘Chariots of Fire' (1981), and I had the soundtrack album (by Vangelis) as a kid – I particularly like ‘Abrahams Theme’, in C#m. Curiously, The Three Fates ends in a Db major tonality, so I feel a tidy segue coming on… and equally curiously, the Keith Tippett vamp uses the same 2 chord movement as Abraham’s Theme (tonic chord to flattened submediant), so another segue is possible… Serendipity? You couldn’t make this stuff up…

Other elements of the programme will be drawn from the array of pieces that I’m currently working on – not least the long-awaited Prelude 1 op 16 by Scriabin (yay!). The Elton John cover (wait and see) is a request – ‘keeping the customers satisfied’, as Paul Simon might have said… and the Meade Lux Lewis blues is a transcription I made back in the early 1990s. Here's the original -

There will be a couple of other pieces too, and some improvisation... you'll have to come along to find out...

Incidentally, if you want to hear me playing a single pass of 'Vexations' - the music of the Lockdown - then tune in for the next ‘Lockdown Vexations’, which is broadcast on 12th July. Submissions are invited, if you feel moved to have a go – see satievexations.art . After all this, I’ll definitely be encouraging George to get involved!

There will be a couple of other pieces too, and some improvisation... you'll have to come along to find out...

Incidentally, if you want to hear me playing a single pass of 'Vexations' - the music of the Lockdown - then tune in for the next ‘Lockdown Vexations’, which is broadcast on 12th July. Submissions are invited, if you feel moved to have a go – see satievexations.art . After all this, I’ll definitely be encouraging George to get involved!

BLOG UPDATE (March 2021) -

The 'Pianoscapes' concerts from 2020 that are referred to in this blog can now be viewed here -

June: (featuring 'the Three Fates') -

June: (featuring 'the Three Fates') -

and July (featuring 'Fracture') -

'Fracture' and 'The Three Fates' (or rather, two of them!) can also be viewed here -

| | |

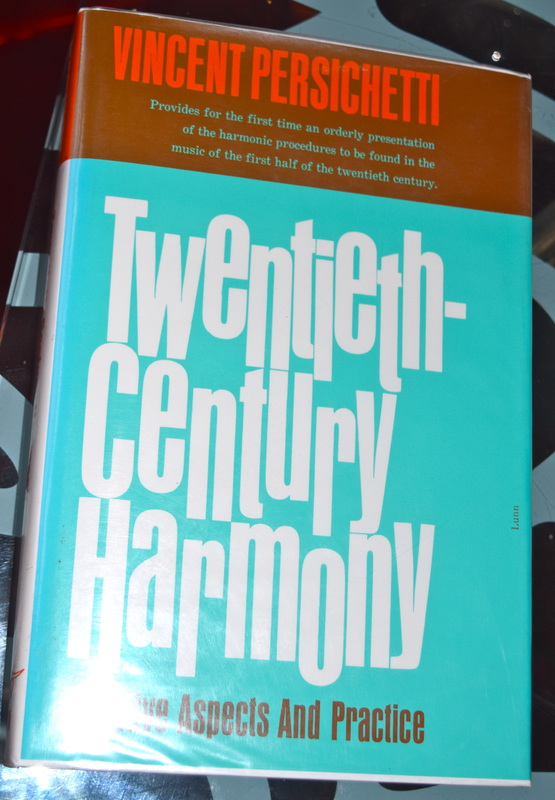

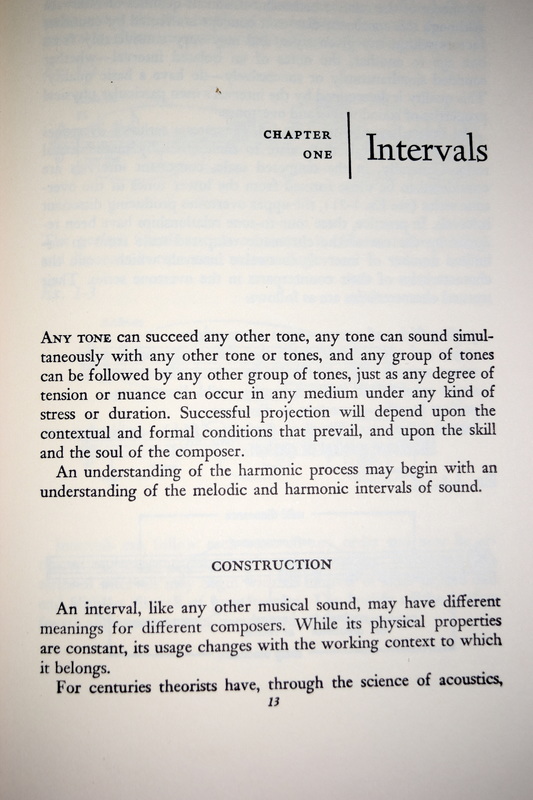

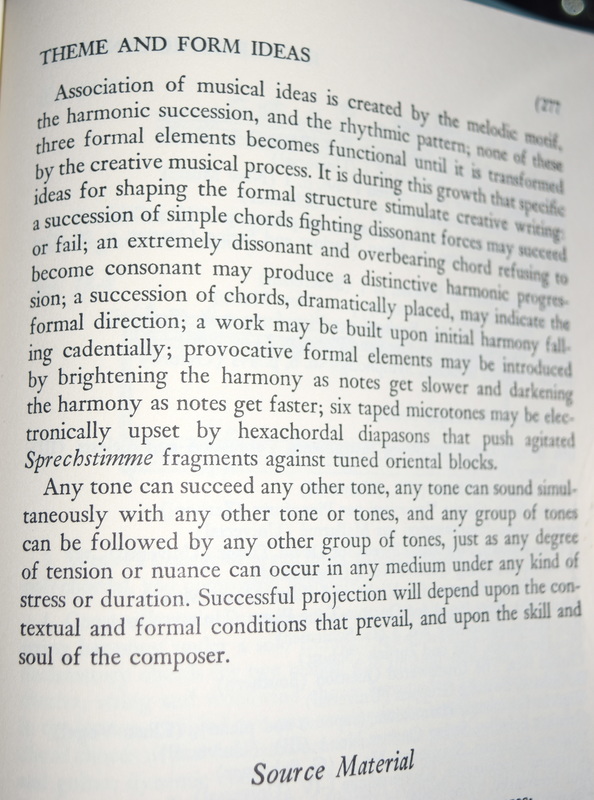

| | Yesterday I had that great feeling of really being inspired by the work of another musician – not just ‘appreciating’ their music, or being impressed by its ‘cleverness’, ‘virtuosity’, or ‘depth of emotional content’ etc – but being shown new things that spark off an excitement and urgency to get busy in the composing lab with my own work. I’m talking about the hour I spent with sound designer Tom Angell showing me around some of his recent creations with Pro Tools and Logic – it opened my mind to ways of working beyond the limited understanding of the software I’ve had until now. It’s like the ways I used to approach working with 4-track tape recorders – I’d never thought to use that approach with digital technology. Inspiring! We tend to get locked into the way we do things, to stick with what we know. To be shown something outside this framework can really blow a wind of change or at least fresh air through the way we do or see things. I’ve long been fond of Vincent Persichetti’s ‘Twentieth Century Harmony’, a book I first came across when I was a spotty O level student in the mid 1980’s. The thing I like best about it is that it begins with a paragraph that reads ‘Any tone can succeed any other tone, any tone can sound simultaneously with any other tone or tones, and any group of tones can be followed by any other group of tones, just as any degree of tension or nuance can occur in any medium under any kind of stress or duration. Successful projection will depend upon the contextual and formal conditions that prevail, and upon the skill and soul of the composer”. Wow. Stop for a minute and re-read that. This is the opening gambit of a music theory textbook. Basically, Vince seems to be saying ‘Never mind Eric Taylor, or those outlawed consecutive octaves in your Bach chorales – anything goes’. The book then goes on, for well over 200 pages, to explore the 20th C developments in approaches to the elements of music – intervals, scale materials, chords by 3rds, chords by 4ths, polychords, rhythm, textures, tonalities… it present a whole bunch of ideas that my spotty teenage self was becoming increasingly aware of on my journey into music. However, the book concludes with exactly the same paragraph that it began with, giving a sense of negating everything between the covers that might suggest a ‘dogma’ or ‘right way of doing things’. This had a huge influence on me – yes, I’d been devouring the likes of King Crimson, Derek Bailey and Company, Ligeti and anything weird and ‘out there’ that I could get my mitts on – so this ‘license to do what thou wilt’ came as no surprise, but it was still a revelation to see it so succinctly put in black and white. Perhaps rather dry and academic by today’s standards, the book still represents a potential ‘wind of change’ that could open a whole load of doors for anyone locked in the rut of functional harmony and ‘composing by the rules’. It’s not unlike Brian Eno and Peter Schmidt’s ‘Oblique Strategies’, which came up in two different contexts recently (see Youtube on the left for one of those - by the fabulous Brothers McLeod (http://www.brothersmcleod.co.uk/ ) – the ‘Oblique Strategies’ are a set of ‘prompt cards’ to draw upon when inspiration runs dry: a prod or a nudge from the outside, to inspire movement. Which brings us at last to my last example (phew). It was great to get feedback from a piano student on Monday, that she had got home ‘full of beans and enthusiasm!’, inspired by the things we’re working on. H has recently started playing again after too many years away from the piano; she thought that the repertoire from her past – bits of Beethoven, half-started Chopin pieces etc – would be enough for her to continue to chip away at, plus maybe an Einaudi or Nyman piece for a change. She didn’t bargain for me throwing her the curveball of coaxing her into reading chord symbols (she didn't think she could do it) and encouraging her to explore rather than just ‘read’ - so that she could experiment with Bowie’s ‘Life On Mars’, or find herself tackling the colourful, Scriabin-esque harmonies of Bill Evans… she’s now got a license to push beyond the confines of what she knew, and to explore whole new landscapes. She’s taken a step outside that circle of familiarity; that freshening breeze is blowing through her time at the piano. |

| | Last night, by chance, and late, I ended up watching a documentary about Shostakovich and his 7th Symphony (‘Leningrad’) – http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06vkbcs - an incredible story about famine, totalitarianism and the power of music. I’ve been a fan of Shost’s music since I was a music student: I played a couple of Preludes as a young teenager, before I really knew anything about the man and his music – but their chromatic ‘weirdness’ and their intensity was enough to keep me interested at that time… then we studied the 5th Symphony at A level, and I gained new understandings and insights. I have Andy K to thank for introducing me to more of his music at Uni… It was there too that I first heard the 8th Quartet, played by a quartet of fellow students, and its bleak beauty in the light of the context of its creation struck me to the core. How ironic then that that very work should end up on the Edexcel A Level syllabus that I taught to several cohorts of students over the years – a privilege to introduce others to that amazing work… I always delivered those sessions with a lump in my throat and tears in my eyes, as the power of the music was undeniable. Anyhow… Shost’s music has been on the piano stand at Aphelion Towers of late – I’m planning to include a couple of the op.87 preludes and fugues in my All Saints concert, if time permits to ‘get them down’ enough (I’ll be lucky!!). So how come the ‘timely’ Shostakovich on telly? And the recent release of Julian Barnes’ acclaimed new novel ‘The Noise of Time’, a ‘fiction’ about Shostakovich and the ugly situation in which he found himself, being compelled to join the Communist Party and kowtow to Stalin against his artistic and moral judgement? Is there an anniversary I’m not aware of? Dunno, but now seems as good a time as any to be listening to his music. It carries messages of despair & hope, it can be ugly and utterly beautiful… it is always carefully crafted and cleverly deploys compositional techniques familiar to lovers of Bach and Beethoven whilst being totally of it’s own time. It’s very ‘Cold War’ but hey, what times are we living in now if not ‘war’ and a very ‘cold’ one at that? For those who have yet to meet his music, my recommendations would be – The Piano Quintet – amazing compositional technique and graceful symmetries, eg; in the final few movements. Symphony #5 – from the Soviet bombast of the Finale to the unsettling yet heart-mangling angst in the 3rd movement; String Quartet #8 – dedicated to ‘the victims of fascism & war’ and written after witnessing the destruction of Dresden (supposedly as a final letter before committing suicide, which he didn’t do!); and piano pieces – the ones I tend to play are the same two Preludes (op. 34, written in the winter of 1932/3) that I played all those years back as an intrigued teenager under the watchful ear of Mary K Stevens – nos. 7 & 14 - and Prelude & Fugue 1 and 4 from op.87 (although Prelude 5 and 12 are favourites to play too) – rather more involved and it’s these that I have in mind for All Saints. All Shost’s music have those windy, never-ending chromatic melodies that unsettle and seem so evocative of Cold War uncertainty and paranoia; and he also has a ‘motif’, DSCH (Dmitri Schostakovich!) that he uses as a compositional basis for a lot of his music, making it almost a 4-dimensional puzzle for those who enjoy seeking out and analysing the music… I’ve also been impressed recently by the playing of Valentina Lisitsa, who plays a lot of Shost’s music. Have a listen to her rendition of his Piano Sonata 2 – make sure that you read the lengthy and impassioned ‘sleeve note’ on the Youtube posting. A final word: Dmitri Shostakovich’s musical inheritors in the next generation included Alfred Schnittke and Galina Ustvolskaya, both now deceased (already!). The music of both these composers is amazing – challenging, yes; radical, yes; powerful, certainly. For pianists, fiendish. But worth checking out: it’s a dark and lonely journey, but one well worth making. |

Details

Archives

September 2022

July 2022

June 2022

February 2022

June 2020

February 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed